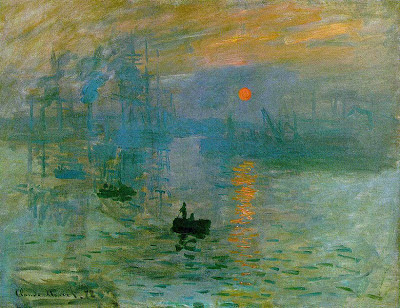

My hatred of painting and drawing seemed to feed a teenage devotion to photography. I snapped photographs by the hundred, capturing moments, getting across ideas when possible. "Painting," I would say, "was something people did before they had cameras." When college began, the profusion of Monet’s "water lilies" posters, usually bad copies that made these paintings look like muddy messes, did little to spark any interest in the other visual arts. "I hate Monet," I told my college girlfriend, who had the ubiquitous waterlily print on her wall. "You’re an idiot," she returned, annoyed. "Who do you like?"

I thought about it, studied some of the hated paintings, and determined grudgingly that I liked Salvador Dali. His uncanny paintings spoke to the phase of life I was in, the disturbed adolescence where the boundaries of society had been distorted by too much knowledge. The real world stretched like taffy and holes opened into alternate dimensions in Dali’s paintings, much as they were doing in my mind. Besides, they were of things that could not be photographed, of the universe of madness, of symbols, and of hyper reality. What I really hated, I decided, was that Impressionist twaddle that took the natural world and dipped it in blurry fish oil.

This preference continued until the millennium, when after spending New Year’s Eve in London, two friends and I traveled to Amsterdam. The Van Gogh Museum was one of our stops, and as we wandered around I was shocked at the thick, nearly three-dimensional paint that gave such texture and luminosity to the landscapes of Provence. I had recently read Irving Stone’s classic biographical novel, Lust For Life, and had been moved and impressed by the story of Van Gogh’s persistent toil. But now I saw that work’s results in all its glory, and it was not the fuzzy nonsense I thought it was. I stared and stared and began to wonder if I had been wrong all this time.

I framed a print of Van Gogh’s Wheatfield With Crows and hung it over my bed. I read art books, paging through collections of works at the library, and gradually absorbed enough to appreciate the differences, realizing that now I could pass that academic decathlon test without guessing. I visited museums near my home, expanding my appreciation and respect to other Impressionists like Camille Pisarro, Paul Cezanne, John Singer Sargent, and Winslow Homer. I found that for many years in the nineteenth century the majority of people had felt the same way I had as a child, and indeed some still did. These Impressionist paintings were like fine wine or cheese, something that the sugar-cravings of youth do not allow for, and only after my palate had been trained had I fully understood their genius.

I have even made my peace with Monet, coming to love his eye for color and light, finding new visual notes every day. My wife and I have included prints of three of his lesser known masterpieces in our house: The Boat Studio, Fisherman's Cottage on the Cliffs at Varengeville, and Fishing Boats at Sea, 1868. This turn-around is probably quite typical. Our maturity of eye parallels the maturity of spirit, and though art appreciation can be as fickle as the fads of technology and toys, the Impressionists have beaten the initial criticism and thrived for over a hundred years. There are reasons for that victory, for why great art lasts, and as adults we should try to discover them.

First published at Hackwriters.